South Sudan

In 2024, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) ran 12 regular and five emergency projects in South Sudan, providing general and specialist healthcare and mental health support. Our teams responded to the growing needs caused by ongoing conflict, displacement, flooding, and disease outbreaks, in a context marked by insecurity, reduced humanitarian funding, and a fragile health system.

803,600

803,6

334,100

334,1

84,800

84,8

28,500

28,5

16,800

16,8

11,200

11,2

5,830

5,83

4,840

4,84

2,360

2,36

We operate one of our largest assistance programmes worldwide in South Sudan, responding to the many health needs resulting from ongoing conflict, displacement, recurrent floods, and disease outbreaks. All these issues are compounded by a marked decrease in international funding for humanitarian and development programmes, and the precarious state of the national healthcare system.

In 2024, it remained highly dangerous for humanitarian organisations working in South Sudan. During the year, MSF staff were killed inside their communities during intercommunal conflicts, and we had to suspend activities in some locations following attacks.

Disease outbreaks

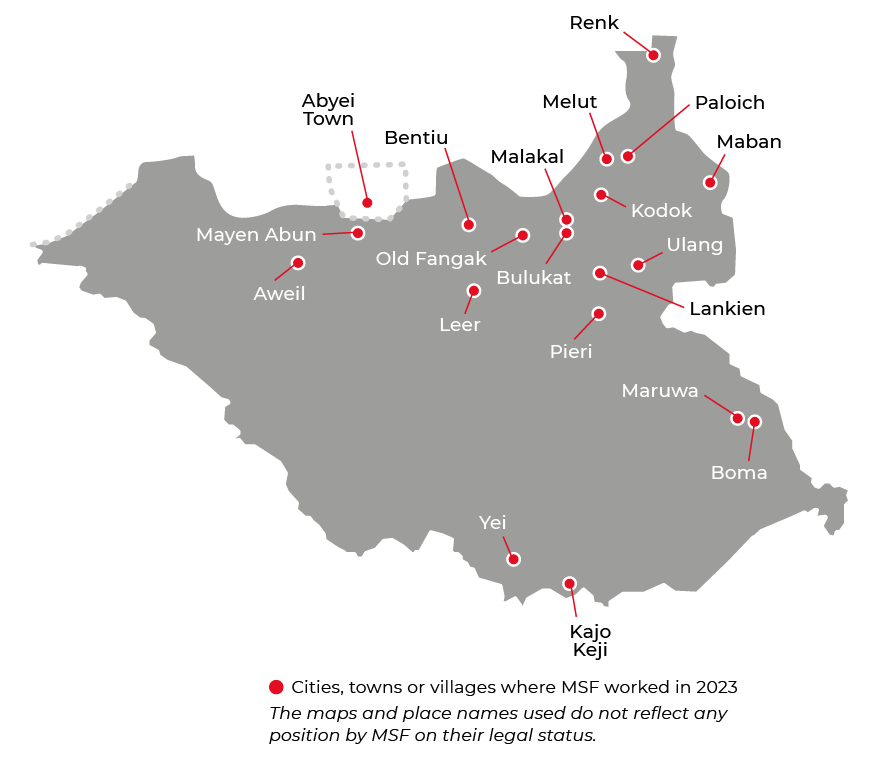

A cholera outbreak was declared on 28 October at the border town of Renk, which hosts refugees and returnees from Sudan. By the end of the year, it was still spreading, and had affected seven states. Our response included setting up cholera treatment centres and units, water and sanitation activities, active case finding, surveillance, and supporting the rollout of oral cholera vaccination campaigns.

In Fangak county, Jonglei, MSF successfully completed a nine-month hepatitis E vaccination campaign, the first to ever be conducted during the acute stages of an active outbreak, and in such a hard-to-reach area.

There were numerous surges in malaria cases across the country in 2024, especially during the rainy season. Flooding also increased incidence rates, as areas of stagnant water encouraged the proliferation of mosquitoes, and drove up numbers of severe illness, as the floods impeded access to treatment centres. In Aweil State hospital, we saw a huge rise in admissions of children who had developed severe malaria because they could not get early treatment at basic health facilities. During the peak in September, admissions had doubled compared to 2023. We opened additional test-and-treat sites to treat simple cases, and expanded the hospital’s malaria ward from 72 to 94 beds. Despite this, the hospital was still stretched beyond capacity, forcing our teams to treat patients in corridors. Earlier in the year, during the annual hunger gap, we also saw an unusually high number of admissions of children suffering from severe acute malnutrition, requiring us to increase the capacity of the intensive therapeutic feeding centre from 22 to 44 beds.

From July, MSF started to implement preventive measures to mitigate malaria, by supporting the Ministry of Health to roll out the R21 malaria vaccine in the counties with the highest burden of the disease, including Twic and Aweil. In addition, we provided seasonal malaria chemoprevention ahead of the peak malaria season, to protect the most vulnerable against the deadly disease.

Flooding

In 2024, South Sudan once again experienced severe and widespread flooding, especially during the rainy season, which had a devastating impact on communities across the country. In Old Fangak, we launched activities to help prevent the town from flooding. As well as installing water gauges and training the community to monitor rising water levels, we worked with other organisations to reinforce the mud levees.

The floods also significantly heightened the risk of water-borne diseases, such as cholera and typhoid, posing a serious threat to public health.

We built a 20-bed field hospital in New Fangak as a precaution, in case Old Fangak hospital flooded. Although not originally intended for this purpose, its presence proved invaluable during the cholera response.

Impact of the war in Sudan

MSF began activities in response to the massive influx of people fleeing the conflict in Sudan in May 2023. We have continued to run medical and humanitarian services for refugees, returnees, and host communities in several regions, including Renk and Bulukat in Upper Nile state, the Abyei Special Administrative Area, and the capital, Juba.

By the end of 2024, nearly one million people had crossed into South Sudan since the war began, according to the UN. In December 2024 alone, the upsurge in violence in some areas of Sudan forced over 120,000 people to seek refuge across the border, mostly in Renk county. MSF responded in informal settlements, such as Girbanat, Gozfami, and Atam, by sending mobile clinics to deliver basic healthcare, truck in water, and set up other water and sanitation infrastructure. We continued to run our stabilisation centre at the Joda crossing point.

In Renk Civil hospital, our team started providing pre- and post-operative care for war-related injuries, in partnership with the International Committee of the Red Cross. Following the influx of refugees in December, we had to set up 17 additional tents to accommodate the increase in patients.

Transition to Bentiu state hospital

In August, we started the gradual transition of healthcare services from Bentiu camp hospital to Bentiu state hospital, and expect this process to be completed by the end of 2025. In October, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, we opened a 48-bed paediatric unit refurbished by our team at Bentiu state hospital, and started seeing patients. By transferring these services, MSF and the Ministry of Health aim to work together to maintain and enhance healthcare provision in Unity state.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI) for snakebites

MSF continued to work with the University of Geneva and the South Sudanese Ministry of Health to improve snake species identification, using an AI tool. This innovative approach, which is being piloted in Twic and Abyei, aims to increase knowledge of local snakes, and raise awareness among medical staff and communities, and improve the treatment of snakebites.

MSF Academy for Healthcare

MSF’s Academy for Healthcare is working to address the critical shortage of qualified healthcare professionals that has long plagued South Sudan. In 2024, the Academy continued to offer tailored training programmes for nursing and midwifery, as well as scholarships for Juba College of Nursing and Midwifery.

1983

1983

3,814

3,814

€119.3 M

119.3M

South Sudan Government Blocking Opposition-Held Areas from Humanitarian Access

MSF begins supporting surgical services at Malakal Teaching Hospital, Upper Nile State

South Sudan: MSF Evacuates Staff from Lankien Healthcare Facility Following Airstrikes

Left behind in crisis: Escalating violence and healthcare collapse in South Sudan